Note: Names of organizations, offices, departments, etc. in the article are as of when the article was first published.

Miyasaka Brewery located in Suwa is one of Nagano’s leading sake breweries and is well known for its brand called “Masumi”. Every year fans from across the country look forward to the release of Masumi’s shinshu (sake nouveau) named “Arabashiri”. Miyasaka brewery has been using T&D data loggers for a number of years to manage temperature during the brewing process. So we paid them a visit at the beginning of the pressing of this year’s sake to talk with Executive Master Brewer Mr. Kenji Nasu, and Fujimi Master Brewer Mr. Atsushi Nakano about how they are using our products.

| Date | November 2019 |

|---|---|

| Places | Miyasaka Brewing Co., Ltd. Fujimi Brewery: Fujimi-shi, Suwa-gun, Nagano Prefecture Suwa Brewery: Motomachi, Suwa-shi, Nagano Prefecture |

| Models in Use | TR-71wf, TR-52, RTR-71, etc. |

| Purpose | Mainly for temperature management during the making of koji (malted rice) for brewing |

Q: First of all, can you tell us a little about your sake brewery?

Mr. Nasu: It was founded in 1662 as a small scale local brewery.

A major turning point came in 1919 when the current president’s grandfather, Masaru Miyasaka, selected a 28-year-old named Chisato Kubota to be brew master. The story goes that the two of them went around the country searching out advice and techniques for making high quality sake.

And slowly slowly after doing this again and again their techniques improved, the sake got better tasting and sales went higher and higher. But the biggest leap forward came in 1946 at the National Sake Appraisal. Masumi took all of top three spots.

At that time, there was a national research institute aiming to improve the quality of sake and stabilize production. Researchers from there came to investigate the reasons why Masumi had achieved such high accolades. While looking through the tanks in the warehouse they discovered the existence of a new yeast they named “Masumi kobo” but now is called “sake yeast No.7”.

This and other sake yeasts are currently under management of the Brewing Society of Japan and a system is in place whereby members can purchase any of the yeasts they oversee for use in brewing. Currently there are nineteen yeasts numbered from 1 to 19 under their control; but even after almost 80 years since discovery about 60% of brewers across Japan use Masumi’s No.7 sake yeast.

Mr. Nasu: The positive appraisal we received and the discovery of the No.7 yeast made our sake brewery famous and sales grew with it.

As the name Masumi spread throughout Japan, the increasing demand from all over the country grew. To meet that demand, in 1982 Miyasaka built a new brewery and warehouses in Fujimi and production began under both locations.

Q: I have heard that in the Masumi line of sake, the sake nouveau called “Arabashiri” is quite popular, can you tell us more about it?

Mr. Nakano: Each year we start receiving brown rice after harvest in September, mill the rice and then start the brewing process. From that first rice, we get a finished product in the middle of November. And we start selling that freshly unpasteurized sake called “Arabashiri” made from that year’s harvest.

Mr. Nasu: One of this first things our current company president put our energy into was selling freshly pressed unpasteurized sake. He felt that the liquor industry needed a sense of seasons, and started selling the first sake made with new rice of each year, naming it “Arabashiri.”

Mr. Nakano: In those days, it was quite a risk to sell and distribute fresh unpasteurized sake.

Sake is inherently perishable and can go off quite easily.

Therefore usually it is sterilized twice, once just after pressing and once more just before bottling. But the more you heat and sterilize, the more the unique fresh flavor and aroma is lost.

Masumi’s “Arabashiri” and other fresh sake are not heat-sterilized at all, so they remain easily perishable.

Despite that fact, makers want their customers to enjoy the flavor and aroma of fresh sake.

At first, when refrigerated transportation was not yet developed, customers were also taking a large risk in buying this type of sake.

Mr. Nasu: Nowadays, with improvements in refrigerated delivery the sale of fresh sake has become commonplace.

Other sake brewers have even started selling products with the same name of “Arabashiri”. The word “arabashiri” is a general term in sake brewing for the product of the first pressing, so the name itself can’t be registered. But I think we were the first company to spread this type of sake and use the word arabashiri in a name for this type of sake.

Q: Can you tell us what kind of temperature management is necessary when producing sake?

Mr. Nakano: There are three key steps to making sake: first is “koji” (a species of rice mold), second is “moto” (the starter culture) and third is brewing. If you can grow good “koji”, then you can create great sake.

“Koji” is a mold culture unique to Japan and is an essential part of not only making sake, but also, in making seasonings such as soy sauce, miso, and vinegar.

The role of koji in sake brewing is to produce saccharification enzymes to dissolve and convert rice starch into sugar.

Once the koji has dissolved the rice into sugar, a microbial yeast called “kobo” is necessary to ferment the sugar and turn it into alcohol.

To increase the kobo yeast, a starter culture called “shubo” or “moto” is made by adding koji, steamed rice, and water to the kobo yeast.

Once the “moto” is well made, then more koji, steamed rice and water are added to scale up to the next stage. This is called “shikomi” or preparation. At Miyasaka Brewery a three-stage mashing process is used; scaling up at each stage.

After the mashing process is completed, their resulting “moromi” or mash is left to sit and allowed for rice to dissolve. The first pressing of “moromi” is “Arabashiri” that was mentioned earlier.

Mr. Nakano: Since the quality of the “koji” greatly affects the character of sake, the idea is that if you can make good “koji”, you can make good sake.

There are various steps in the process of making this so important “koji”, and one key point is temperature control. In particular, temperature is an important key in proceeding from step to step.

Of course, temperature control is also required when making the starter culture and the sake mash, but we use T&D loggers mainly during the “koji” making process.

After steaming the rice and bringing it into the “koji” room, we propagate our “koji” over a three-day period. There are tasks that need handled during all three days, we use T&D loggers to manage temperature over that period and specifically watch temperatures to decide when it is the right condition to do which task.

Without some device like these loggers we would just be guessing.

Q: How did you decide on our products?

Mr. Nakano: There really weren’t any good compact thermometers with an external sensor being used in the brewing industry by koji makers; the ones we had easily broke. It seems like they broke almost every year. And then I saw T&D loggers in some catalog. The cost was of course higher than for an instrument that just measures temperature, but since you could also record data with it we decided to give it a try. The sensor part for most of the thermometers I had used until then often broke off and were pretty much useless. Compared to those both the bodies and sensors are rugged and durable and have not broken at all. Moreover, another good thing is that the sensors can be easily replaced. We have used them since the early on. The first ones were blue and waterproof; we bought a lot of those.

Mr. Nasu: And then the wireless models came out and we bought those right away. That was more than 20 years ago.

After some time passed, the brewing equipment wholesalers would bring the loggers by and try selling them to us saying “You should take a look at these new products”. We would laugh and reply with a sense of superiority “We have been using them for a long time already”.

Mr. Nakano: The fact that the temperature data could be recorded and looked at later was also a huge plus. Until then, we had to check the thermometer at each point in the process and log it down by hand, but since the logger was also recording all the time, it saved us a lot of work. At that time it was a great breakthrough for us.

Mr. Nasu: Also the reaction time is quick. During one stage, when the temperature drops to a certain level, we need to cover the “koji” with a cloth as soon as possible and let it rest. Once you get used to it, you can touch the “koji” and know when the time is right. But for our younger brewery staff it is necessary to check the temperature display and carry out their tasks accordingly. There are many slow response thermometers, but T&D’s loggers respond quickly so we can be sure when to act. Even now, we use your loggers for this at the Suwa brewery.

Q: Do you use different models at each brewery?

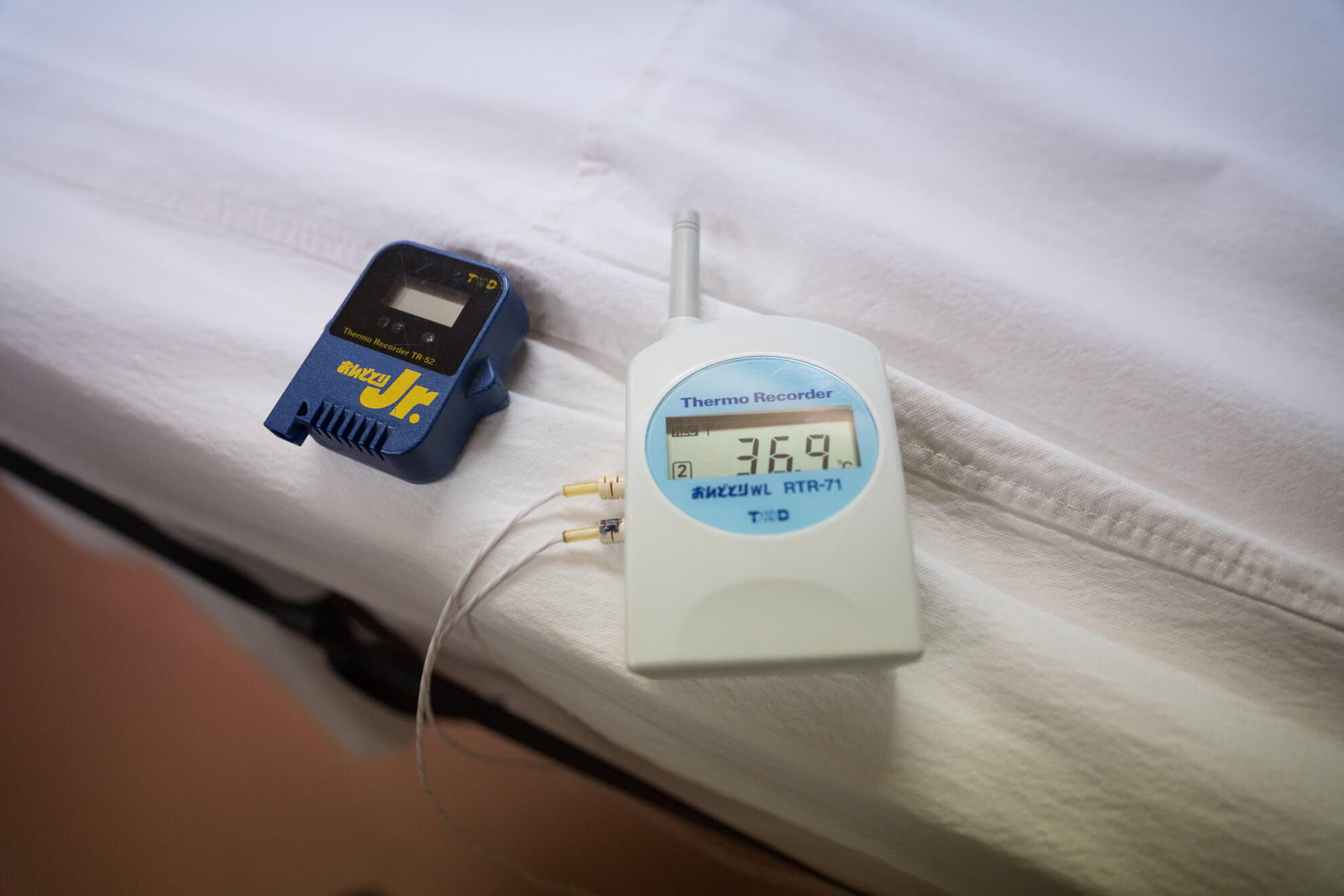

Mr. Nasu: We still use TR-52 and RTR-71 in Suwa, because they never breakdown!

Mr. Nakano: At Fujimi we also use a newer model, the TR-71wf, so that we can send data to the cloud for checking on the Internet.

―― It is quite moving to think that tree generations of loggers (our first small waterproof type, our first wireless type and the more recent cloud compatible type) are being used to assist in the “koji” making at two different locations.

Mr. Nakano: In sake brewing as a whole, the life of sake depends on temperature, so we take it seriously and monitor it closely.

Q: Is all the “koji” making done by hand?

Mr. Nakano: At the Fujimi brewery we do use some machines, but basically it is all manually done.

At some breweries “koji” is made using automation, but we still get our hands into it at each point along the way.

We feel that only by actually touching the product with your own hands and looking at it with your own eyes can you be sure that you are making something good.

Q: Are there any other points that Miyasaka Brewery are especially particular about?

Mr. Nasu: As we talked about earlier, the No.7 yeast was discovered here. There was a time when we used various yeasts, but we are now in the process of shifting back to our roots by switching to only using No.7 yeast. And we are pushing the No.7 yeast itself as a brand. Recently almost all of the products we are making are made with No.7 yeast.

Sakes made for contests may have an advantage using a newer yeast with a stronger aroma and low acidity, but for your everyday table sake, I think that No.7 yeast, with its light fragrance and moderate acidity is more suitable. I think the fact that the No.7 yeast is still being used by a lot in sake breweries nationwide shows that to be true.

Of course the No.7 yeast is an association controlled yeast and can be obtained and used by any brewery that is a member. But I think the meaning is a bit different when it is used by the brewery where it originated.

Mr. Nakano: So, even though it is a slightly old fashioned yeast, I am taking a fresh look at it and tinkering with it to find a new way to make delicious sake. The time for a change is here and we’re experimenting with new ways to make use of our heritage. The “kobo” or yeast is one of the most important factors in determining the quality of sake, and with changes to the yeast come great changes to the flavor and tone of the sake.

Mr. Nasu: There are so many factors that determine the taste of sake, from rice varieties and degree of rice polishing to rice washing, soaking, steaming time, and so on. Of course, the way the koji is made and the temperature during fermentation naturally affects the final outcome as well. Even the way it is pressed produces great differences.

And or course another important factor is the starter culture “shubo” or “moto”; the quality of the sake changes greatly depending on how it is made. Since we have decided to use our No.7 yeast here, the variations that can occur here have been narrowed down. However, we want to boldly state that “This is what Masumi tastes like!” and it is here where that is decided.

Q: But isn’t using only the No.7 yeast considerably constraining?

Mr. Nasu: The yeasts are living things; they are constantly splitting and multiplying. Our No.7 yeast has been preserved in a traditional agar medium, so over the many years of repeated splitting and reproduction it of course has degenerated. The character of the yeast is not the same as it was when first discovered.

Still, among the hundreds of millions of “kobo” selected according to certain characteristics, there are some that still exhibit the same properties from olden times. We fish them out one by one, check the tastes, select the good yeasts, and store them at -80°C (-112°F).

So we still retain a number of yeasts with similar character to the original. These No.7 yeasts are different from those commonly found and shared in the brewing industry; they are only our No.7 yeasts. It is with these that we hope to build new variations that will make for spectacular and unique sake.

Q: Lastly, I would like to ask you brewers if you have any tips for enjoying sake or any recommended ways of drinking sake?

Mr. Nakano: Every brewery makes various types and brands and there are a lot of different breweries; that makes for a huge variety of sake available.

If you are going to drink sake I think it is a good idea to not just drink one brand at a time, but rather drink two or more at the same time and compare them. That way you can see which one goes well with which food.

And by comparing two or more, you can better find which one tastes best to you. I really think this is a fun and interesting way to enjoy sake.

Some people just “drink by ear”, meaning they hear or read info about what people say about a certain sake and that influences their tastes.

I think it is better you search out and find your favorite according to your own taste buds.

―― I guess most people are, as you say, “drinking by ear”, but isn’t it hard to judge which one is good by yourself?

Mr. Nasu: I think that by drinking several at a time and comparing you will come to find the ones that you find delicious, unless of course sake itself doesn’t suit you. And once you find some that you truly like a whole new world will open up.

Mr. Nakano: There is also a chance to encounter new foods as well.

It may be OK to just line up some different kinds and drink them, but if you pair sake with different snacks and food it totally changes the equation.

Strangely enough, a brand that may have tasted good when drinking by itself may not taste so good when paired with some foods. Sake has an interesting deepness to it.

I think it is best to try sake with some food or snacks and see what you think.

Mr. Nasu: Mainstream sake these days is very fragrant and a bit sweet. That may make delicious for one or two cups taken alone but are not so good for drinking with food. There was a time when we were also making sake that garnered good results in contests and was said to be delicious, and sake for pairing with food took a secondary role.

Recently as we returned to the sole use of our No.7 yeast I realized that more acid was necessary for sake to match well with food. If you make sake with the No.7 yeast, you will get more acidity. I think this is one of the reasons why No.7 yeast is used for making every day table sake and it is to this origin that we are now returning.

That concluded our interview with Mr. Nasu and Mr. Nakano.

I was struck by this seemingly contradictory and difficult idea about how “returning to the origin is challenging”. I took it to mean that as a manufacturer you can stick to your policy because you are constantly rethinking what is truly necessary and what is not.

As a writer working for a data logger maker, I will be sure to keep a watchful eye on the brand development of Miyasaka Brewery. And as a sake fan, I will be sure to keep tasting that development as well.

After the interview we went on a tour of both the Fujimi and the Suwa facilities.

Fujimi Brewery

At the Fujimi Brewery, Mr. Nakano explains about sake rice.

Giant rice milling machine.

Checking the polishing conditions of the milled rice.

Sake rice waiting to be steamed.

Inside of the “koji” room.

TR-71wf measures and records the temperature during “koji” making and automatically sends it to the cloud.

Inside the same “koji” room.

Logger being used to measure temperature while moving the “koji”.

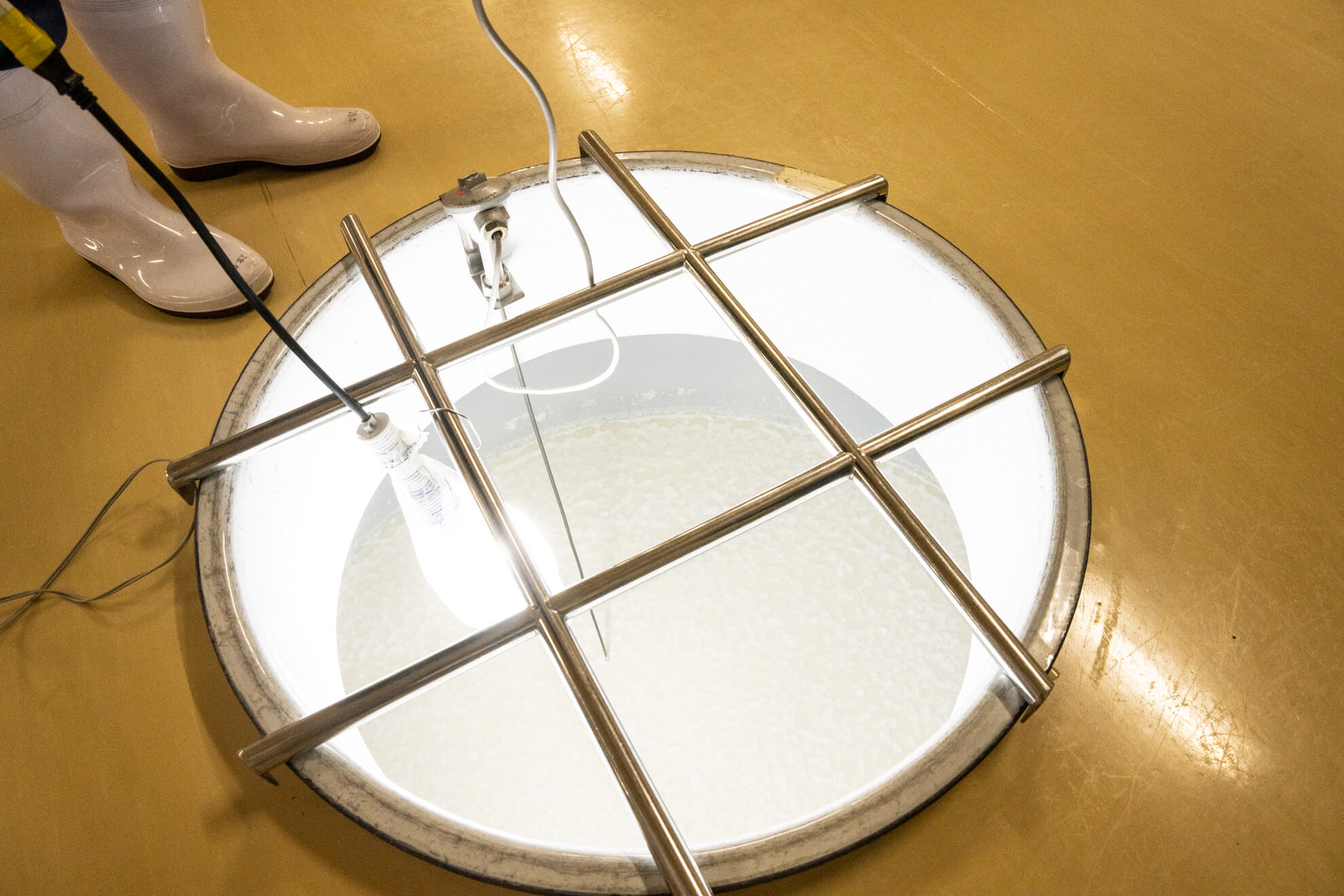

Tank for making the starter culture “shubo” or “moto”.

Bubbling of fermentation.

Preparation tank.

Fermentation proceeds in three stages.

With no oxygen, dropping would mean instant death.

Suwa Brewery

Brewery shop “Cella Masumi” connected to the Suwa Brewery.

On hand are original brands such as a sparkling Junmai sake which has won awards in overseas contests.

Ninju Inari Shrine and a monument to “Birth of the No.7 Sake Yeast” inside the Suwa Brewery

Exterior of the “koji” room at the Suwa Brewery

Inside the “koji” room.

TR-52 and RTR-71, models from more than 20 years ago, are still going strong. They have been treated with the utmost care.

Preparation tanks

The symbol of Masumi, the No.7 yeast, was discovered here.

Miyasaka Brewing Company, Ltd.

Go to Masumi’s Website